Through the eyes of docents, a closer look at the Mint’s permanent collection

More than 50 docents make up part of The Mint Museum family. A docent is a museum guide, usually a volunteer, who can share knowledge on everything from the Art of the Ancient Americas at Mint Museum Randolph to the Craft+Design galleries at Mint Museum Uptown. And best of all, the tours are free to visitors. Museum docents share their favorite artworks and insights on the Mint’s permanent collection below.

[cs_divider color=”#afafaf”]

Sabrina Gschwandtner (American, 1977– ). Quilt Film Quilt, 2015, 16 mm polyester film, polyester thread. Museum Purchase: Funds provided by the Founders’ Circle Ltd. in honor of Fleur Bresler. 2016.42

Quilt Film Quilt by Sabrina Gschwandtner

One of my favorite pieces is Quilt Film Quilt by Sabrina Gschwandtner (Gish-wandt–ner). The piece is a quilt made of old 16-millimeter film that is cut and sewn together to form a quilt. The piece is amazingly beautiful and looks totally different when viewed from afar versus up close. It is also a wonderful homage to the history of handicraft in the United States. Throughout the years, quilts have played many roles in our society, including a way for women to express information about their lives. Quilts were also created to raise funds for causes, such as women’s suffrage, and with the advent of quilting bees, quilting became a social outlet. What I love most about quilts is their ability to provide warmth and spread love.

—Lindsey Edmondson

[cs_divider color=”#afafaf”]

Grace Hartigan (American, 1922–2008). Scotland, 1960, oil on canvas. Gift of the Mint Museum Auxiliary, 2013.33. © Estate of Grace Hartigan

Scotland by Grace Hartigan

Grace Hartigan’s painting Scotland in the Contemporary Gallery is one of my favorite pieces in the Mint Collection. I find that spending time looking at this painting slowly is a transformative experience. The large size of this work is engaging. The abstract style, as well as the use of the color blue, encourages meditation and introspection. I am also drawn to the spontaneity and gestural mark making, and the emotional expression and sense of spirituality.

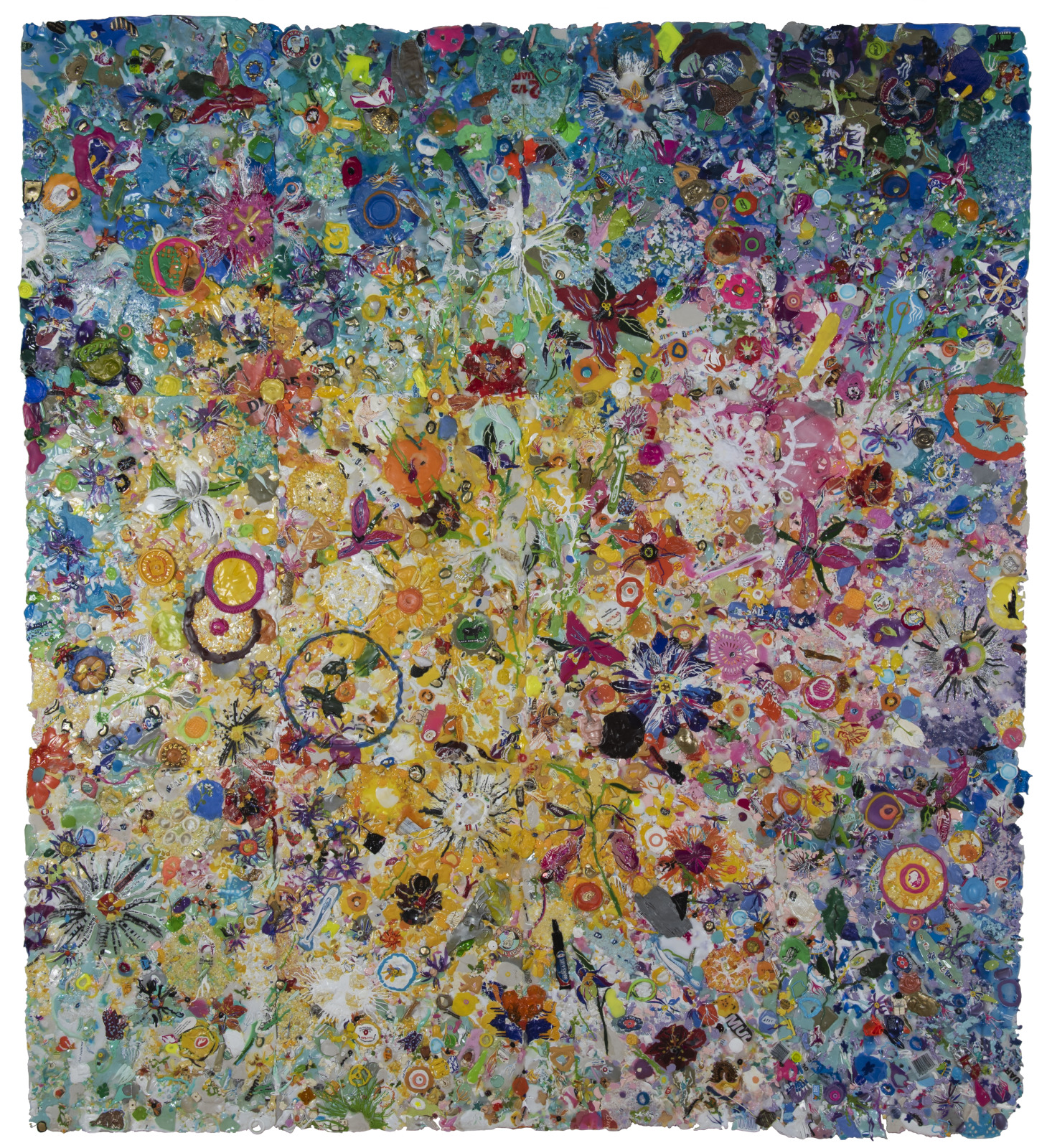

Sheila Gallagher (American, 1966- ). Ghost Orchid Plastic Nebula, 2018, melted plastic on armature. Museum purchase with funds provided by Wells Fargo. 2018.48

Ghost Orchid Plastic Nebula 2018 by Sheila Gallagher

Created by melting plastic packaging and other plastic objects otherwise destined for the trash, Ghost Orchid suggests that transformation can result in great beauty. The bright colors and cheerful arrangement remind me of a field of wildflowers or a glorious bouquet.

You must look closely to understand what this work is about. Viewed from a distance, it looks like an abstract painting. That would be enough, but to fully appreciate Gallagher’s message and her mastery of materials you must spend some time with the work—plus, you have to find the ghost orchid. Ghost Orchid Plastic Nebula asks us to consider the objects that are part of our everyday lives and what happens to them when they are no longer of use. By including the rare and endangered ghost orchid in the work, the artist reminds us of the fragility of our ecosystems. Good things to keep in mind as we find ourselves evaluating what really is important.

Check out the video Chronical Trash Talk: Artists Are the Best Recyclers for a glimpse of Sheila Gallagher at work and for some very heavy thoughts on trash.

—Renee Reese

[cs_divider color=”#afafaf”]

David Drake (American, 1800–75). Five Gallon Jar, 1864, stoneware, alkaline glaze. Museum Purchase: Exchange Funds from the Gift of the Mint Museum Auxiliary and Daisy Wade Bridges in memory of Walter and Dorothy Auman. 2002.112

Five-Gallon Jar by David Drake

I absolutely love the large piece of pottery Five-Gallon Jar on display at Mint Museum Uptown. The Mint has many great pottery pieces, but this pot is especially special because of its maker, his story, and his personality. The pot was made on March 19, 1864 by a master potter named Dave. We know this because it’s inscribed on the pot. It also says “lm,” which refers to Dave’s master, Lewis Miles. Dave signed many pots, which was highly unusual for the time. As an enslaved African American in South Carolina it was illegal for Dave to write. His signed pots show an independence and a spirit, as well as courage.

Several of his pots also had short poetry. Three of my favorites are:

“Another trick is worse than this, Dearest Miss, spare me a kiss” – August 26, 1840.

“I wonder where is all my relations, Friendship to all – and every Nation” – August 16, 1857.

“I made this jar all of a cross, if you don’t repent all will be lost” – May 3, 1862, during the Civil War when many people were dying.

Dave’s personality comes through in his poetry, and in the Mint’s example, I can see it in his large scripted signature, “Dave.” Five-Gallon Jar is one of the last he signed. He died at age 64. It’s an incredibly unique gift to see, to absorb, and to appreciate the craftsmanship and poetry in Dave’s work.

—Ross Loeser

[cs_divider color=”#afafaf”]

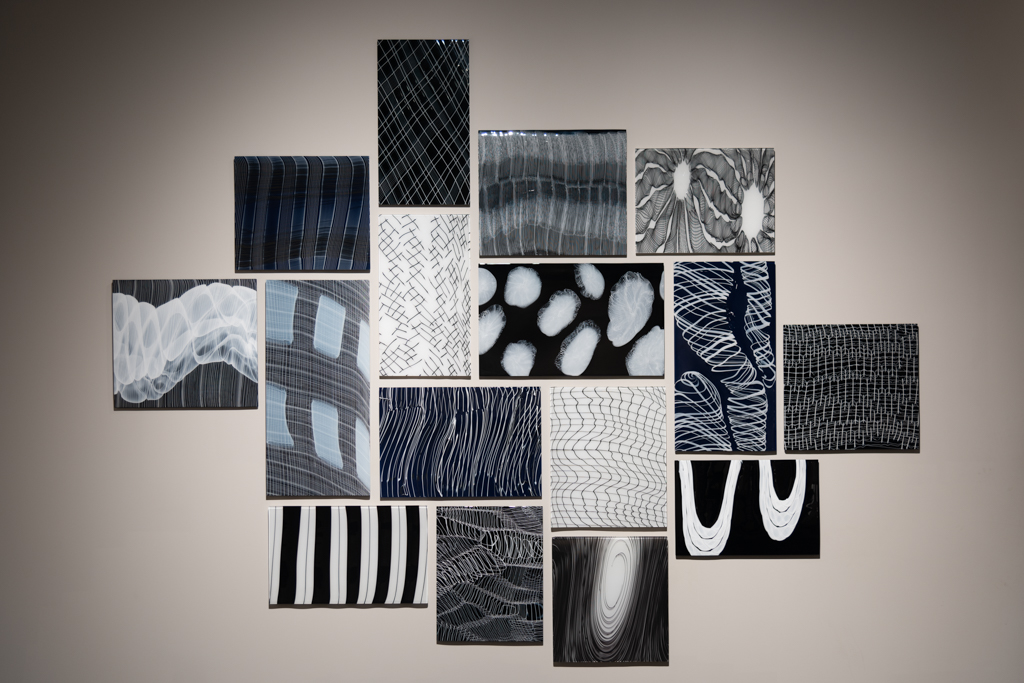

Nancy Callan (American, 1964– ). Spin, Weave, Gather, 2018, blown and slumped glass. Gift of lead donors Lorne Lassiter and Gary Ferraro; Judy and John Alexander, Sandy Berlin, Linda and Bill Farthing, The Founders’ Circle, Libba and Mike Gaither, William Gorelick, Barbara Loughlin, Jancy and Gilbert Patrick, Mark Ridenhour, Vicki Jones, Yvonne and Richard McCracken, Sara and Bob McDonnell, Britt and Greg Hill, and Deborah Halliday and Gary Rautenstrauch. 2019.8A-O

Spin, Weave, Gather by Nancy Callan

One of my favorite pieces of art at The Mint is Spin, Weave, Gather by Nancy Callen. As you approach this splendid wall-hung exhibit, you can’t immediately tell that you are looking at glass, and most especially, that the flat, textural pieces are blown glass. In 2016, Nancy Callan, a Seattle-based glass artist, entered a residency here in North Carolina at STARworks. During that time, she learned about the history of the textile industry in North Carolina. The transformation of cotton from plant to thread to woven fabric captured her imagination because her work in glass has been informed by textile patterns, as well as the process of fabric production. In this work, Callan celebrates the alchemy of starting with sand and ending up with crystal – much the same as the magical journey of a plant seed ending up as a beautiful piece of fabric.

Her process requires a skilled team of glass blowers to make the caliber of work that she produces. She says working with her team is like a ‘jazz band’ – there is a leader, but everyone has a role to play and a time to ‘shine’. They work to music, any kind of music, which she believes creates a rhythm that they all respond to. What is so remarkable in this process is that the glass panels start out as large cylinders (like the ones behind her in the picture below). Once these cylinders are completed, the bottoms are cut off and they are returned to the kiln. She cuts along one long side of the cylinder after it begins to soften and as the glass continues to heat, they coax it open and it becomes flat. After the piece is flattened and cooled, it must be cleaned, polished, and fired again. Nancy says this is the process in which artists originally made window panes for buildings.

—toni Kendrick

Nancy Callan in front of the large glass cylinders that are eventually transformed into the glass panels that make up her artwork. Photo courtesy of toni Kendrick

[cs_divider color=”#afafaf”]

Hoss Haley (American, 1961– ). “White Ripple,” 2013, metal. Museum Purchase: Funds provided by Windgate Charitable Foundation. 2013.59. © Hoss Haley 2013

White Ripple by Hoss Haley

I am a big fan of the work of Hoss Haley. I love to bring visitors to see his piece called White Ripple. It is fun to watch the guests study it and figure out how it was made. Hoss takes found objects, (mostly metals) and shapes them into interesting forms. In this case, he went to a junkyard and took the sides off washing machines. The squares are then bolted together and curves are introduced in a circular fashion like you see when something drips into water. He likes to keep the metals raw and unfinished and many of his items rust in outdoor installations. He has several pieces around Charlotte, including a giant bronze hand called Integrity by the Courthouse uptown, and a gargantuan 40-foot tall, 20-ton installation called Old Growth at the Charlotte Douglas airport.

—Laura Lynn Roth

[cs_divider color=”#afafaf”]

James Goodwyn Clonney (American, 1812–67). Offering Baby a Rose, 1857. oil on canvas with an early nineteenth-century frame. Museum Purchase: Exchange Funds from the Gift of Harry and Mary Dalton. 1998.20

Offering Baby a Rose by James Goodwyn Clonney

One of my favorite things about being a docent at the Mint Museum is helping people discover new and fun ways of viewing and thinking about art. One piece I often like to show visitors at our Uptown location is Offering Baby a Rose by James Goodwyn Clonney. I like this piece because it gives me the opportunity to show visitors how to “look” at art with more than just their eyes, but using their other senses as well. For example, I often ask visitors what they smell when they look at this piece. At first, I get some strange reactions, but then I pass around a bar of rose-scented soap and they immediately get it.You could also think about how the rose feels. Are the petals soft and silky, or are there thorns on the flower’s stem?

Another question to think about is: What do you hear when you look at this piece of art? Do you hear birds chirping or a light breeze blowing through the trees? Or do you hear the clanging of dishes as breakfast is being made? By using all of your senses you can come to a more nuanced understanding of works of art. Engaging smell, sound, and touch allows you to create new interpretations of Offering Baby a Rose.

—Lindsey Edmondson